Your message has been sent.

CLOSE SIDEBAR

CLOSE SIDEBAR

Brain network clustering and frontal lobe connectivity in Latinx rural farmworker children and urban non-farmworker children

David Baskin

Poster Title: Brain network clustering and frontal lobe connectivity in Latinx rural farmworker children and urban non-farmworker children

Student: David Baskin, Class of 2024

Faculty Mentor and Department: Paul Laurienti, MD PhD, Department of Radiology

Funding Source: Department of Medical Education, Wake Forest School of Medicine

ABSTRACT

Background: Latinx rural farmworker children are a high-risk group for exposure to agricultural pesticides. Recent analysis has shown chemical exposure to be stratified by a greater detection of organophosphate (a neurotoxic agricultural pesticide) in rural farmworker children compared to urban non-farmworker children. In contrast, urban non-farmworker children were found to be highly exposed to other pesticides (pyrethroids and organochlorines). Exposure to neurotoxic pesticides is concerning for both populations as it may cause deleterious effects on neurodevelopment.

Hypothesis: We hypothesized that brain networks would differ between the two populations of Latinx children, with rural farmworker children exhibiting lower brain network clustering and reduced connectivity of the Default Mode Network (DMN) compared to urban non-farmworker children.

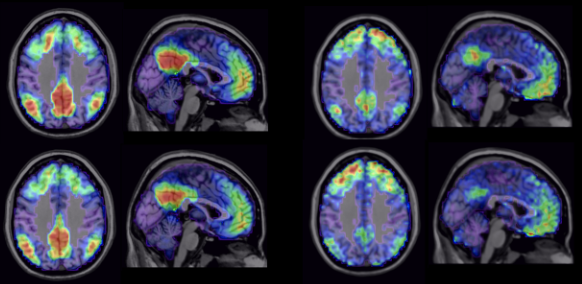

Methods: Whole brain networks were constructed from resting state fMRI data for forty-eight rural farmworker children and thirty urban non-farmworker children (age 8). These networks were then clustered using modularity into network communities which yielded data driven analogs of large-scale brain networks defined in the literature. The DMN was the focus for analysis as prior literature suggests that organophosphates may alter the development of this circuit. The consistency of the DMN network community for each cohort was determined using a statistic called Scaled Inclusivity that describes spatial overlap of the measured DMN community with a pre-defined template. The connectivity of the frontal lobe, a major component of the DMN, was assessed and regions that were two network steps away (second-order connections) were compared between groups. Scaled Inclusivity for the DMN and 2nd Order Connectivity for the rural farmworker children and urban non-farmworker children were compared using permutation tests.

Results: The network analyses clearly demonstrated that the DMN community was intact in both study populations. Contrary to our hypothesis, there was no significant difference between the groups (p=0.582). Brain maps of the frontal lobe connectivity suggested group differences in the projections to the posterior brain areas, however, these findings were not significant (p=0.841).

Conclusions: Although this analysis did not yield statistically significant differences in brain network connectivity between Latinx rural farmworker children and urban non-farmworker children, visualizations of the data did show subtle differences. While it is reassuring that differences in pesticide exposures have not yet been shown to result in significant variation, intra-cohort variability may factor into the results. In addition to a consistent expression of neuropathology, an increased variability within a cohort may represent effects of exposure. It is possible that both pesticide-exposed populations in our study have experienced detrimental effects on neurodevelopment. Future work should compare brain development in children having high pesticide exposure to children having low pesticide exposure. As more longitudinal data is collected, temporal changes in development may be identified. Our findings should not deter the continued implementation of efforts to reduce neurotoxic pesticide exposure in North Carolina children.

Source of mentor’s funding or other support the at funded this research: Preventing Agricultural Chemical Exposure among North Carolina Farmworkers (PACE5) study Grant Number R01ES008739 National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS).

Powered by Acadiate

© 2011-2024, Acadiate Inc. or its affiliates · Privacy