Your message has been sent.

CLOSE SIDEBAR

CLOSE SIDEBAR

Relationship Between Race, Barriers to Prenatal Care, and Receipt of Prenatal Care Among Pregnant Individuals at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist

Morgan Yapundich

Background: Inadequate prenatal care is associated with several adverse pregnancy outcomes including increased risk of preterm birth, small for gestational age infants, intrauterine fetal demise, and infant death. In 2018, 16.4% of live births were delivered by mothers with inadequate prenatal care, with black and Native American women exhibiting the highest rates of inadequate prenatal care. Forsyth County, North Carolina (NC) consistently reports high rates of preterm birth, with 12.2% of women in 2018 experiencing preterm births compared to the NC average of 10.4%. While previous studies have elucidated that race and income are associated with lower receipt of prenatal care, the factors underlying low rates of prenatal care in Forsyth County remain poorly characterized. The objective of this study was to assess rates of prenatal care receipt and identify barriers to care among individuals receiving childbirth services at the Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist (AHWFB) hospital.

Hypothesis: Non-white individuals experience more barriers to care and are less likely to receive adequate prenatal care than white individuals, and a greater number of barriers to care is associated with less adequate prenatal care.

Methods: A convenience sample of 200 individuals receiving childbirth services at AHWFB were surveyed regarding their prenatal care, barriers to prenatal care, and demographic factors including age and income. Individuals eligible for the study spoke English or Spanish, were aged 18 or older, and at least 35 weeks gestation at delivery. After obtaining verbal consent from study participants, a 14-question survey was administered by a trained research assistant.

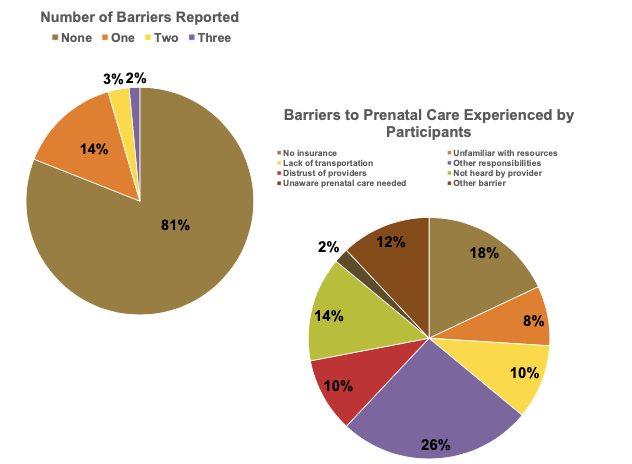

Results: In terms of barriers to care, 19% of participants reported at least one barrier to prenatal care, with the most common barrier cited as other competing responsibilities such as childcare or work. There were no significant differences in reported barriers to care between white vs. non-white participants or between participants with low (defined as a family income of less than $40,000 annually) vs. middle or high family incomes. The overall prenatal care receipt rate was 81%, 87%, and 88% in the first 28 weeks, between 28 and 36 weeks, and after 36 weeks gestation, respectively, with 76% of participants receiving adequate prenatal care at all three time periods. The rate of adequate prenatal care among non-white participants in the first 28 weeks of pregnancy was 88%, which was significantly lower than their white counterpart’s rate of 98% (p<.01). Interestingly, there were no significant differences in prenatal care rates between white and non-white participants after 28 weeks of pregnancy. Additionally, participants of lower income were significantly less likely to receive prenatal care throughout their pregnancies. Finally, participants who reported barriers to care were more likely to report inadequate prenatal care at all three gestational periods, but the relationship was moderated by race in the first two gestational periods.

Conclusions: In our sample, relatively few barriers to care were reported, and the prevalence of barriers didn’t differ by race or income, while adequate prenatal care rates were relatively high. However, non-white participants who experienced barriers were more likely to report inadequate prenatal care in the first 28 weeks and between 28 and 36 weeks of their pregnancy compared to white participants who also reported barriers. These findings suggest that white individuals might have resources to overcome barriers that are unavailable to non-white individuals.

Source of mentor’s funding or other support that funded this research: none

Powered by Acadiate

© 2011-2024, Acadiate Inc. or its affiliates · Privacy